This is Part 1 of a four-part series on sexual objectification–what it is and how to respond to it.

The phrase “sexual objectification” has been around since the 1970s, but the phenomenon is more rampant than ever in popular culture–and we now know that it causes real harm.

What exactly is it, though? If objectification is the process of representing or treating a person like an object, then sexual objectification is the process of representing or treating a person like a sex object, one that serves another’s sexual pleasure.

How do we know sexual objectification when we see it? Building on the work of Nussbaum and Langton, I’ve devised the Sex Object Test (SOT) to measure the presence of sexual objectification in images. In it, I propose that sexual objectification is present if the answer to any of the following seven questions is “yes”:

1) Does the image show only part(s) of a sexualized person’s body?

Headless women, for example, make it easy to see them as only a body by erasing the individuality communicated through faces, eyes and eye contact:

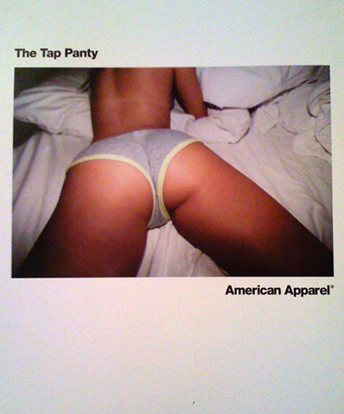

We achieve the same effect when showing women from behind, which adds another layer of sexual violability. American Apparel seems to be a culprit in this regard:

Covering up a woman’s face works well, too:

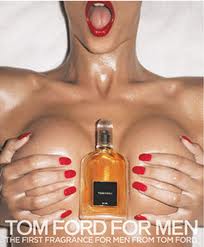

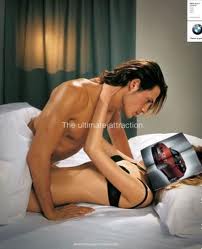

2) Does the image present a sexualized person as a stand-in for an object?

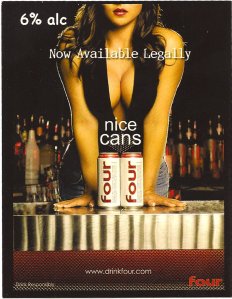

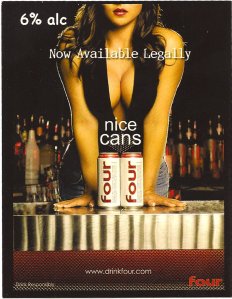

The breasts of the woman in this beer ad, for example, are conflated with the cans:

Likewise the woman in this fashion spread in Details, in which a woman becomes a table upon which things are perched. She is reduced to an inanimate object, a useful tool for the assumed heterosexual male viewer:

Interchangeability is a common advertising theme that reinforces the idea that women, like objects, are fungible. And like objects, “more is better,” a market sentiment that erases the worth of individual women. The image below, advertising Mercedes-Benz, presents just part of a woman’s body (breasts) as interchangeable and additive:

This image of a set of Victoria’s Secret models, borrowed from a previous Sociological Images post, has a similar effect. Their hair and skin color varies slightly, but they are also presented as all of a kind:

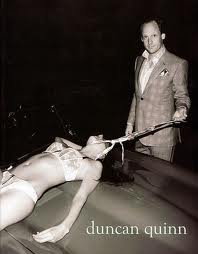

4) Does the image affirm the idea of violating the bodily integrity of a sexualized person who can’t consent?

In this “spec” ad for Pepsi (not endorsed by the company), a boy is being given permission by the lifeguard to “save” an unconscious woman:

Likewise, this ad shows an incapacitated woman in a sexualized position with a male protagonist holding her on a leash. It glamorizes the possibility that he has attacked and subdued her:

5) Does the image suggest that sexual availability is the defining characteristic of the person?

This American Apparel ad, with the copy “now open,” sends the message that this woman is open for sex. She presumably can be had by anyone.

6) Does the image show a sexualized person as a commodity that can be bought and sold?

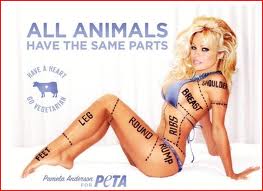

By definition, objects can be bought and sold, and some images portray women as everyday commodities. Conflating women with food is a common sub-category. This PETA ad, for example, shows Pamela Anderson’s sexualized body divided into pieces of meat:

And this album cover shows a woman being salted and eaten, along with a platter of chicken:

In the ad below for Red Tape shoes, women are literally for sale and consumption, “served chilled”:

7) Does the image treat a sexualized person’s body as a canvas?

In the two images below, women’s bodies are presented as a particular type of object: a canvas that is marked up or drawn upon.

The damage caused by widespread female objectification in popular culture is not just theoretical. We now have more than 10 years of research demonstrating that living in an objectifying society is highly toxic for girls and women. I’ll describe that research in Part 2 of this series.

Sexual Objectification Part 2: The Harm.

This is the second part in a series about how girls and women can navigate a culture that treats them like sex objects. (Part 1 can be found here.)

Sexual objectification is nothing new, but this latest era is characterized by greater exposure to advertising and increased sexual explicitness in advertising [PDF], magazines, television shows, movies [PDF], video games, music videos, television news, and “reality” television.

In a culture with widespread sexual objectification, women (especially) tend to view themselves as objects of desire for others. This internalized sexual objectification has been linked to problems with mental health (clinical depression, “habitual body monitoring”), eating disorders, body shame, self-worth and life satisfaction, cognitive functioning, motor functioning, sexual dysfunction [PDF], access to leadership [PDF] and political efficacy [PDF]. Women of all ethnicities internalize objectification, as do men to a far lesser extent.

Beyond the internal effects, sexually objectified women are dehumanized by others and seen as less competent and less worthy of empathy by both men and women. Furthermore, exposure to images of sexually objectified women causes male viewers to be more tolerant of sexual harassment and rape myths. Add to this the countless hours that some girls/women spend primping to garner heterosexual male attention, and the erasure of middle-aged and elderly women who have little value in a society that places women’s primary value on their sexualized bodies.

Beyond the internal effects, sexually objectified women are dehumanized by others and seen as less competent and less worthy of empathy by both men and women. Furthermore, exposure to images of sexually objectified women causes male viewers to be more tolerant of sexual harassment and rape myths. Add to this the countless hours that some girls/women spend primping to garner heterosexual male attention, and the erasure of middle-aged and elderly women who have little value in a society that places women’s primary value on their sexualized bodies.

Theorists [PDF] have contributed to understanding the harm of objectification culture by pointing out the difference between sexy and sexual. If one thinks of the subject/object dichotomy that dominates Western culture, subjects act and objects are acted upon. Subjects are sexual, while objects are sexy.

Pop culture sells women and girls a hurtful fiction that their value lies in how sexy they appear to others; they learn at a very young age that their sexuality is for others. At the same time, sexuality is stigmatized in women but encouraged in men. We learn that men want and women want-to-be-wanted. The yardstick for women’s value (sexiness) automatically puts them in a subordinate societal position, regardless of how well they otherwise measure up. Perfectly sexy women are perfectly subordinate.

The documentary Miss Representation has received considerable mainstream attention, one indicator that the public is now recognizing the damaging effects of sexual objectification of women.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6gkIiV6konY

Widespread sexual objectification in U.S. popular culture creates a toxic environment for girls and women. The next two posts in this series provide ideas for navigating objectification culture in personally and politically meaningful ways.

Photo of Playboy Bunnies via Wikimedia Commons.

Sexual Objectification Part 3: Daily Rituals to Stop.

his is the third installment of a four-part series about how girls and women can navigate a culture that treats them like sex objects. (See Part 1, Part 2.)

There are four damaging daily rituals of objectification culture we can immediately stop engaging in to improve our health.

1) Stop seeking random male attention.

Most women were taught that heterosexual male attention is our Holy Grail before we were even conscious of being conscious, and its hard to reject this system of validation. But we must. We give our power away a thousand times a day when we engage in habitual body monitoring so we can be visually pleasing to others. The ways in which we seek attention for our bodies varies by sexuality, race, ethnicity and ability, but the goal too often is to attract the male gaze.

Heterosexual male attention is actually pretty easy to give up, when you think about it. First, we seek it mostly from strangers we will never see again, so it doesn’t mean anything in the grand scheme of life. Who cares what the man in the car next to you thinks of your profile? You’ll probably never see him again. Secondly, men in U.S. culture are raised to objectify women as a matter of course, so an approving gaze doesn’t mean you’re unique or special. Thirdly, male validation through the gaze alone doesn’t provide anything tangible; it’s fleeting and meaningless. Lastly, men are terrible validators of physical appearance, because so many are duped by make-up, hair coloring and styling, surgical alterations, etc. If I want an objective evaluation of how I look, a heterosexual male stranger is one of the least reliable sources on the subject.

Suggested activity: When a man catcalls you, respond with an extended laugh and declare, “I don’t exist for you!” Be prepared for a verbally violent reaction as you are challenging his power as the Great Validator. Your gazer likely won’t even know why he becomes angry, since he’s simply following the societal script that you’ve interrupted.

2) Stop consuming damaging media.

That includes fashion, “beauty” and celebrity magazines, along with sexist television programs, movies and music. Beauty magazines, in particular, give us very detailed instructions on how to hate ourselves, and most of us feel bad about our bodies immediately after reading. Similar effects are found with television and music video viewing. If we avoid this media, we undercut the $80 billion a year Beauty-Industrial Complex that peddles dissatisfaction to sell products we really don’t need.

That includes fashion, “beauty” and celebrity magazines, along with sexist television programs, movies and music. Beauty magazines, in particular, give us very detailed instructions on how to hate ourselves, and most of us feel bad about our bodies immediately after reading. Similar effects are found with television and music video viewing. If we avoid this media, we undercut the $80 billion a year Beauty-Industrial Complex that peddles dissatisfaction to sell products we really don’t need.

Suggested activity: Print out sheets that say something subversive about beauty culture, like “This magazine will make you hate your body,” and stealthily put them in front of beauty magazines at your local supermarket or corner store.

3) Stop playing the tapes.

Many of us girls and women play internal tapes on loop for most of our waking hours, constantly criticizing the way we look and chiding ourselves for not being properly pleasing in what we say and do. Like a smoker taking a drag first thing in the morning, many of us are addicted to this self-hatred, inspecting our bodies first thing as we hop out of bed to see what sleep has done to our waistline. Self-deprecating tapes like these cause my female students to speak up less in class. They cause some women to act stupid when they’re not, in order to appear submissive and therefore less threatening. These tapes are the primary way we sustain our body hatred.

Stopping the body-hatred tapes is no easy task, but keep in mind that we would be highly offended if someone else said the insulting things to us that we say to ourselves. These tapes aren’t constructive, and they don’t change anything in the physical world. They are just a mental drain.

Suggested activity: Sit with your legs sprawled and the fat popping out wherever. Walk with a wide stride and some swagger. Eat in public in a decidedly non-ladylike fashion. Burp and fart without apology. Adjust your breasts when necessary. Unapologetically take up space.

4) Stop competing with other women.

Unwritten rules require us to compete with other women for our own self-esteem. The game is simple: The prize is male attention, which we perceive as finite, so when other girls/women get attention from men we lose. This game causes many of us to reflexively see other women as natural competitors, and we feel bad when we encounter women who garner more male attention than we do. We walk into parties and see where we fit in the “pretty girl pecking order.” We secretly feel happy when our female friends gain weight. We criticize other women’s hair and clothing. We flirt with other women’s boyfriends to get attention, even if we’re not romantically interested in them.

Unwritten rules require us to compete with other women for our own self-esteem. The game is simple: The prize is male attention, which we perceive as finite, so when other girls/women get attention from men we lose. This game causes many of us to reflexively see other women as natural competitors, and we feel bad when we encounter women who garner more male attention than we do. We walk into parties and see where we fit in the “pretty girl pecking order.” We secretly feel happy when our female friends gain weight. We criticize other women’s hair and clothing. We flirt with other women’s boyfriends to get attention, even if we’re not romantically interested in them.

Suggested activity: When you see a woman who triggers competitiveness, practice active love instead. Smile at her. Go out of your way to talk to her. Do whatever you can to dispel the notion that female competition is the natural order. If you see a woman who appears to embrace the male attention game, recognize the pressure that produces this and go out of your way to accept and love her.

Photo of Stop sign via Wikimedia Commons.

Sexual Objectification Part 4: Daily Rituals to Start.

The fourth and last in a series about how girls and women can navigate a culture that treats them like sex objects. (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3). This post details some daily rituals that women can start doing to interrupt damaging beauty culture scripts.

1) Start enjoying your body as a physical instrument. Girls are raised to view their bodies as a project they have to constantly work on and perfect for the adoration of others, while boys are raised to think of their bodies as tools to master their surroundings. Women need to flip the script and enjoy our bodies as the physical marvels they are. We should be thinking of our bodies as vehicles that move us through the world; as sites of physical power; as the physical extension of our being in the world. We should be climbing things, leaping over things, pushing and pulling things, shaking things, dancing frantically, even if people are looking. Daily rituals of spontaneous physical activity are a sure way of bringing about a personal paradigm shift, from viewing our bodies as objects to viewing our bodies as tools to enact our subjectivity.

1) Start enjoying your body as a physical instrument. Girls are raised to view their bodies as a project they have to constantly work on and perfect for the adoration of others, while boys are raised to think of their bodies as tools to master their surroundings. Women need to flip the script and enjoy our bodies as the physical marvels they are. We should be thinking of our bodies as vehicles that move us through the world; as sites of physical power; as the physical extension of our being in the world. We should be climbing things, leaping over things, pushing and pulling things, shaking things, dancing frantically, even if people are looking. Daily rituals of spontaneous physical activity are a sure way of bringing about a personal paradigm shift, from viewing our bodies as objects to viewing our bodies as tools to enact our subjectivity.

Suggested activity: parkour,”the physical discipline of training to overcome any obstacle within one’s path by adapting one’s movements to the environment,” can be done any time, anywhere. I especially enjoy jumping off bike racks between classes while I’m dressed in a suit.

2) Do at least one “embarrassing” action a day. Another healthy daily ritual that reinforces the idea that we don’t exist to only please others is to purposefully do at least one action that violates “ladylike” social norms. Discuss your period in public. Swing your arms a little too much when you walk. Open doors for everyone. Offer to help men carry things. Skip a lot. Galloping also works. Get comfortable with making others uncomfortable.

3) Focus on personal development that isn’t related to beauty culture. Since you’ve read Part 3 of this series and given up habitual body monitoring, body hatred and meaningless beauty rituals, you’ll have more time to develop yourself in meaningful ways. This means more time for education, reading, working out to build muscle and agility, dancing, etc. You’ll become a much more interesting person on the inside if you spend less time worrying about the outside.

3) Focus on personal development that isn’t related to beauty culture. Since you’ve read Part 3 of this series and given up habitual body monitoring, body hatred and meaningless beauty rituals, you’ll have more time to develop yourself in meaningful ways. This means more time for education, reading, working out to build muscle and agility, dancing, etc. You’ll become a much more interesting person on the inside if you spend less time worrying about the outside.

4) Actively forgive yourself. A lifetime of body hatred and self-objectification is difficult to let go of, and if you find yourself falling into old habits of playing self-hating tapes, seeking male attention, or beating yourself up for not being pleasing, forgive yourself. It’s impossible to fully transcend the beauty culture game, since it’s so pervasive and part of our social DNA. When we fall into old traps, it’s important to recognize that, but then quickly move on through self forgiveness. We need all the cognitive space we can get for the next beauty culture assault on our mental health.